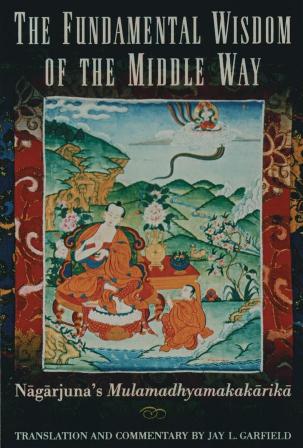

The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamakakarika by Jay L. Garfield

Author:Jay L. Garfield

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 1995-08-30T16:00:00+00:00

Chapter XVII

Examination of Actions and Their Fruits

Arguing for the emptiness of bondage and liberation, however, raises a further question that demands an answer: If there is no real bondage and no real release, what are the effects of our actions? For it would appear, at least given standard Buddhist moral theory and the doctrine of karma on which it is grounded,86 that meritorious actions conduce to liberation and that morally wrong actions increase bondage. Given the emptiness of these latter, an analysis of the consequences of action is in order. Nāgārjuna begins with Buddhist moral truisms, accepted by the Mādhyamika as well as by members of other Buddhist schools. It is important to note that the first nineteen verses of this chapter represent the views of four distinct opponents in order of increasing similitude to the Mādhyamika understanding. Despite the fact that Nāgārjuna sets these views up as targets, however, some of the views the opponents put on the table are, suitably interpreted, shared by Nāgārjuna. Each

can be seen as, despite being inadmissible as a characterization of a nonconventional basis for the relation between action and its effects, a reasonable empirical assessment of at least part of the conventional reality in this domain.

1. Self-restraint and benefiting others

With a compassionate mind is the Dharma.

This is the seed for

Fruits in this and future lives.

2. The Unsurpassed Sage has said

That actions are either intention or intentional.

The varieties of these actions

Have been announced in many ways.

The classification to which Nāgārjuna refers is a partition of actions into mental and physical. Mental actions are mere intentions on this view; physical actions and speech (generally distinguished in Buddhist psychology and action theory) are properly intentional. That is, the latter two involve a mental and a nonmental component; the mental actions only involve a mental component. Verse 3 clarifies this:

3. Of these, what is called “intention”

Is mental desire.

What is called “intentional”

Comprises the physical and verbal.

In the next verse, an opponent uses these truisms as a platform for the defense of the view that actions themselves must remain in existence until their consequences are observed. Actions that derive from renouncing the world are different from those that derive from worldly concerns. This difference in nature, he argues, must explain the difference in their consequences:

4. Speech and action and all

Kinds of unabandoned and abandoned actions

And resolve87

As well as …

5. Virtuous and nonvirtuous actions

Derived from pleasure,

As well as intention and morality:

These seven88are the kinds of action.

The kinds of actions to which Nāgārjuna’s imaginary opponent refers are simply the various kinds of virtuous and nonvirtuous actions. In general, morally good actions are done for the sake of pleasure for others; morally bad actions sacrifice others’ good for one’s own pleasure. The opponent, however, goes further, pointing out that these actions have diverse long-term consequences that must be explained:

6. If until the time of ripening

Action had to remain in place, it would have to be permanent.

If it has ceased, then having ceased,

How will a fruit arise?

The problem is this: Given that the

Download

The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamakakarika by Jay L. Garfield.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9000)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8396)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7130)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6796)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6614)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5784)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5775)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5515)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5190)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4449)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4305)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4275)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4273)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4256)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4250)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4130)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4007)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3963)